A Cobbled-Together Frankenstein of Fragments (rwblog S6E2)

Last updated: 7/17/2024 | Originally published: 1/7/2023

Hello all and welcome back to rwblog. This time I’m revealing my top 10 books and top 5 films of 2022. I was intending to write longer essays for each of these over the holidays, but then it didn’t happen! Instead I just wrote up some quick notes for each of these, because I’d rather get this send out before we get too far into 2023. Sometimes the perfect really is the enemy of the good, or at least the productive.

Note that I’m only including books or films that were new to me this year. On rwblickhan.org you can find my complete book log and film log for 2022!

Books

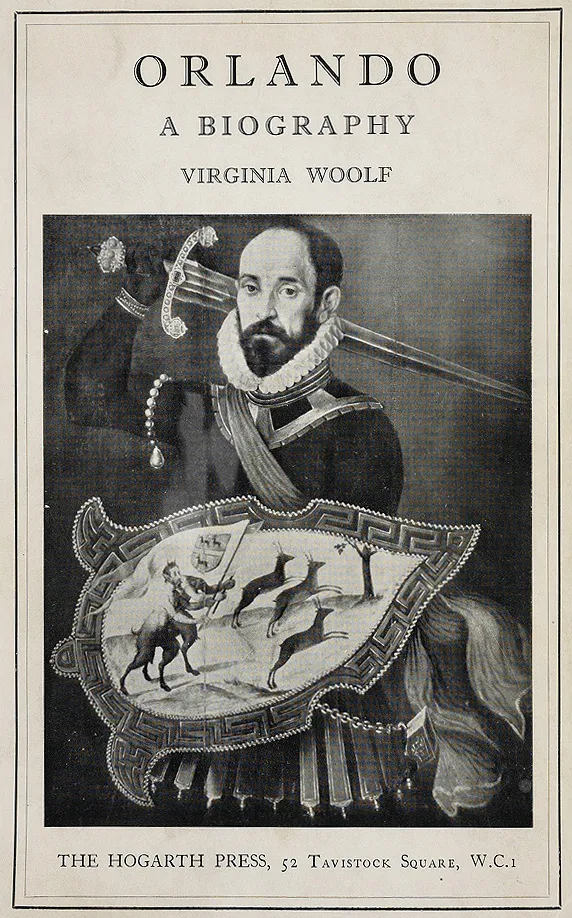

- Orlando: A Biography, Virginia Woolf: Orlando is the strangest and most surprising book I read this year. Woolf is often considered the po-faced doyenne of High Modernism, with 300-page novels consisting of three people thinking really hard about going to a lighthouse. Needless to say, then, it’s something of a surprise to read Orlando, a gorgeous (!), funny (!!) magic realist (!!!) novel following a person who starts as a young man in Elizabethan England and ends as a married woman in the early 20th century and meets most of the luminaries of English literature along the way. It was supposedly written as a love letter to Vita Sackville-West and it has a personal touch that makes it feel confidential — but I’m glad it was published.1

- The Last Unicorn, Peter S. Beagle: A modern classic, in the fullest sense of that word; if Kazuo Ishiguro deserves a Nobel prize, then so does Peter S. Beagle. Sentence-by-sentence some of the most beautiful prose I’ve ever read; every writer would benefit from studying the flow of sentences here. It uses fairy tale to fullest effect, refusing to be tied to a set meaning; this seemingly-simple tale of a unicorn looking for her lost people can be read as everything from amusing picaresque to serious family drama to warning against immortality to Holocaust allegory.

- The Plague, Albert Camus (2021 edition translated by Laura Marris): It doesn’t do this novel justice to say that it’s the best literary representation of a pandemic ever written, although that’s very true. Instead, it’s one of the great — if often neglected — existentialist works, about finding meaning in a meaningless world where God allows innocent children to die. It’s… it’s rough, I’m not going to lie, but it’s a novel I imagine I will be revisiting the rest of my life.

- A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, George Saunders: An introduction to some of the world’s great short stories from a master of the craft.2 This book works on three levels: it collects a series of (mostly) fantastic short stories in their entirety,3 it provides commentary and criticism that deepens the experience of each story, and the commentary itself is artistic non-fiction — yes, that’s right, literary criticism providing an emotional experience in its own right. Every writer should study this collection in depth — I particularly like Saunders’ reframing of Chekhov’s Gun as a “things I can’t help noticing” bucket — but all readers of literature should appreciate it.

- The Sandman, Neil Gaiman: I was always slightly confused what The Sandman was about, because fans typically use a blend of abstract nouns like “dreams” and “the power of storytelling” instead of describing the plot. Now I am one of those fans. The first two volumes are mostly, though not entirely, straightforward horror, but the later volumes expand into a series of deeply heartfelt short stories about, well, dreams and the power of storytelling. If horror isn’t your cup of tea, skip straight to the third or even fourth volume; The Sandman is about vibes more so than strict plot.

- Faust: A Tragedy, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (Norton Critical Edition translated by Walter Arndt): I lied — Orlando is not the strangest work I read this year, Faust is. Initially, I read the translation by Martin Greenberg, who I am convinced hates Goethe as an author — in his introduction, he basically calls Goethe a Nazi — but I had a much better time with the Norton Critical Edition, which helpfully provides a page or two of explanatory notes for each scene. Yes, it’s one of those books, where you really need a page or two of explanatory notes for each scene. That’s because it is, frankly, a mess — a cobbled-together Frankenstein of fragments from across Goethe’s life, combining disparate strands of thought that caught Goethe’s interest over the years, from infanticide to scientific theories of crust formation to neoclassical art. A few scenes were straight up never written; even the scenes that were written are sometimes, uh, difficult, to say the least. I definitely can’t recommend this to, well, almost anyone, though Faust: Part I, featuring the tragedy of Gretchen, definitely has an emotional impact. Still, something about Faust and his relentless striving, always undermined by Mephisto’s insistence on ultimate nihilism, is compelling — compelling enough that I slogged through two full translations of this (fairly long!) poem.

- Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes (unabridged translation by Edith Grossmann): It’s somewhat difficult to recommend the unabridged Don Quixote to the reader of 2022 — it’s something like 800 pages, dense with references to Golden Age Spanish culture and more than a few page-long jokes repeated until the reader is nauseous. You should persevere, though, and discover that Don Quixote is a shockingly modern story — featuring postmodern, meta twists that wouldn’t be out of place in an Italo Calvino story and a perceptive eye for human interaction that, notably, leads to a refreshing lack of misogyny and bigotry (!). The story slowly evolves from a laugh-out-loud4 slapstick comedy to a genuinely touching drama about an idealistic man struggling to find meaning in a disenchanted world.

- The English Understand Wool, Helen deWitt: I don’t want to say anything about this witty little book and ruin the experience, so I’ll just say: deWitt’s The Last Samurai is among my all-time-favorites and this book is only 70 pages with large type, so you can literally read it in an hour or so. There’s nothing to lose!

- The Lathe of Heaven, Ursula K. Le Guin: This is perhaps the most “very Russell” book I read this year. It won’t be for everyone, but if you’re interested in dreams (check), Daoism (check), the nature of power (check), or simply like wild avant-garde stories (check!), then it might be “very you” as well.

- His Dark Materials Book 2: The Subtle Knife, Philip Pullman: I only regret that I came to His Dark Materials as an adult and not an impressionable tween. Had I read this series at age 12 or 13, I have no doubt it would occupy the all-time-favorite position now occupied by The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Unfortunately, as an adult, I can’t help but notice that it’s sometimes just a little bit janky — an “off” line of dialogue here, an underdeveloped character there, a cheap plot trick in between. Nonetheless, I love this series; The Subtle Knife starts at a whippet pace and never slows down, featuring some of the wildest worldbuilding out there — it has witches and steampunk balloons and a knife that can open portals to another world and a war in Heaven and what’s not to love.

“Goethe in the Roman Campagna”, Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1787)

“Goethe in the Roman Campagna”, Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1787)

Films

- Evangelion 3.0+1.01: Thrice Upon A Time: If you know me well enough, this should be no surprise. Although I appreciate the hard-earned happy ending, what really makes this film a masterpiece that stands on its own from the rest of the series is the first half, where Hideaki Anno gives up on the robots and aliens and Christian imagery to tell a Miyazaki-influenced story about a small town struggling to survive after the end of the world as we know it, in a a beautifully anti-catastrophic vision that will only become more relevant as climate change takes over the world. Also, there’s a library in a train.

- Hausu: Hausu is a very silly late-70s Japanese horror B-movie partly written by a 10-year-old. It’s also a strikingly original avant-garde cinematic experiment drawing on a deep well of sadness about the atom bombing of Hiroshima. The miracle of cinema is that these two statements are not contradictory, resulting in what may be my favorite film of all time, if not the best I’ve ever seen.

- Everything Everywhere All At Once: This was pretty much universally declared film of the year and I can only echo it. That said, next time you watch it, consider the lens of neurodiversity! Apparently in early drafts the main character was supposed to have undiagnosed ADHD (which in fact led one of the directors to realize he had it himself) and I think some of that leaked into the final draft.

- Stalker: Many would say Stalker, a 3.5-hour-long film about three guys taking a hike, is a pretentious slog. They might be right! But I think the same way Andrei Tarkovsky did, and a tone poem that’s heavy on striking visuals and Christian symbology and elusive allusions with just enough plot to string it all together fit me just right.

- Andrei Rublev: While Stalker is Tarkovsky’s masterpiece, I’m including Andrei Rublev here for its final scene, featuring a sobbing bell artisan, because it perfectly encapsulates the mixed feelings after completing a major artistic project.

A Random Note from the Archive: “Moby-Dick was not well received its day”

I take a lot of notes, mostly into Obsidian. In each issue of rwblog from now on, I’ll share a random note from the archive!

This month, a note fittingly titled “Moby-Dick was not well received in its day”, based on this r/AskHistorians post. The gist is that Herman Melville actually saw the most success with his first novel, Typee, and even became a 19th-century sex symbol, but his later novels, especially Moby-Dick, were critical and commercial flops; he spent the last years of his life working in obscurity as a customs inspector to pay the bills. He remained only a cult classic — particularly among gay male writers in England, apparently — before his reputation was revived in the 1920s, in part because his writing style was so similar to modernists like… Virginia Woolf!

(I swear I did not rig this to provide a note relevant to this issue!)

Next Time

Among other topics, I want to chat about bicycles for the mind, artificial intelligence as writing compilers, perfect story structures, and second city syndromes!

Footnotes

-

Yes also Virginia Woolf is one of the most famous bipolar people in history so I’m glad I like at least one of her novels 👀 ↩

-

Admittedly, I’m not sure I’ve read a Saunders short story. But he is widely considered a master of the craft. (Sherry likes him!) ↩

-

One of which, Chekhov’s “Gooseberries”, is now among my all-time favorites. ↩

-

Yes, I literally laughed out loud. ↩